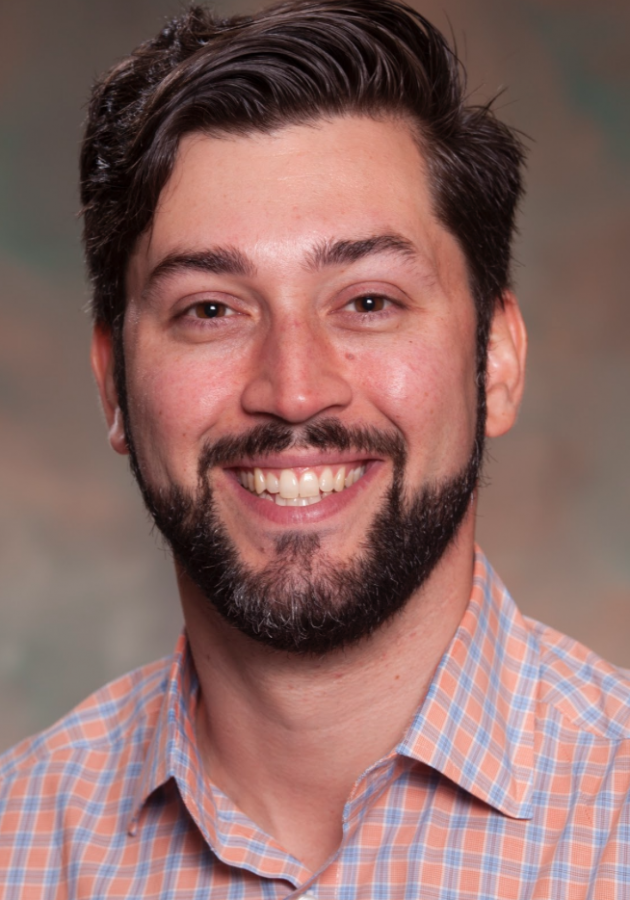

In light of the recent violence in Charlottesville, Virginia, The Coat of Arms sits down with history teacher Ryan Dean, who grew up in Charlottesville, to hear his thoughts about the violence. Photo courtesy of Ryan Dean.

By Connor Van Ligten

It may have been just a statue, but the ideals and history revolving around it called for its removal. When the statue of Confederate Civil War general Robert E. Lee was removed from its resting place in Charlottesville, Virginia, alt-right and neo-nazi protestors eventually attacked anti-racist protestors, resulting in injuries, destruction of property, and even a few deaths. History teacher Ryan Dean, who grew up in Charlottesville and attended the University of Virginia, shared his thoughts on the events in an interview with The Coat of Arms.

CoA: Talking about the events in Charlottesville, was that kind of ideology, that kind of belief, the hatred you saw exhibited by those groups, was that something you ever experienced?

Dean: It’s not something that I experienced in Charlottesville but it is something that I witnessed at the University of Virginia while I was a student. In my second year at the school, this would have been fall of 1999, there was a lot of anti-black graffiti all over the campus. This really surprised me, and what was less surprising was the response by black students. They certainly had a vocal response that year on campus, but black applications dropped by almost 25% the following year. Nobody missed the signals. It was probably done by people who were participating in the march. [I] recall that two of the leaders were UVA alums, and one of them would have been there at the same time I was a student.

CoA: Where do you think those kind of beliefs originate from, and what do you think communities can do to stop that from spreading heavily?

Dean: Other wiser, more knowledgeable people have spoken to the causes of resurgences in white supremacists. We’ve seen lots of heroes in American history since the Civil War that showcase white resentment. A resentment that manifests itself in supremacist ideology. Ultimately, any time you feel threatened, anytime you think that your group or your identity is being fundamentally and dangerously challenged, by institutions in our society or by other members of our society, in a large scale way, you might think, for example, the black lives matter movement, it makes sense that some people would take a more radical approach to showing their discontent, to showing their frustration, to showing their anger.

I think that’s what happened. If we’re talking about Charlottesville specifically, it’s like a lot of Southern towns. It’s a town that’s part white and part black, that has a geographical line of demarcation that separates the [part of the community with more white people] with [the part of the community with more black people]. It’s a relatively liberal town, but it’s a very conservative county. So, anyone who would’ve gone to the University of Virginia like those two protest organizers, those two supremacist ideologues, would have been familiar with the dynamic, would’ve understood that they would have a lot of sympathetic whites in the surrounding area, and probably would have been motivated to hold a university like virginia to stick it to the liberal townfolk. People we call “townies” to use the nomenclature.

And I would have also argued that they probably saw it as a symbolic way to represent the legacy of Thomas Jefferson. I saw some writing about that in the Atlantic, New York Times, Washington Post, and other media outlets. Jefferson, as you know, is a complex historical figure. One the one hand, he is the primary author of the Declaration of Independence, he started the University of Virginia and saw it as a bastion of enlightenment. But on the other hand, it was a school that had its roots in slavery, and he was a man that took advantage of his access to slaves, in ways that have been well-documented, namely his relationship with Sally Hemings, and the mulatto offspring, that interracial union.

I don’t know what communities can do to stop the events. I don’t think there’s a lot you can do to plan to undercut these movements from recurring, but communities can think intentionally about how they want to manage a protest and how they want to manage a mass uprising, and they can think about what should happen in the aftermath of those events. There’s quite a bit of chastising of Charlottesville police officers for being too inactive and not taking an aggressive enough stance, for example, to prevent the driver of that automobile from running into the crowds on 4th street. They did seem overwhelmed by the size of that protest.

Police should probably use that as a case study for how to avoid similar incidents in the future. What will you do when the protesters come to your town?. And secondly, you have to be honest about the legacy of slavery and racial division in the south, you could say that about a lot of places in the north but it’s going to be most acute in the south. The other thing you have to acknowledge, maybe this could be considered something in Charlottesville’s favor, [is that] democracy’s local.

So if you want to see the immediate cause of protest as a fight about the removal of Civil War monuments, you need to address that locally. You need to let towns decide whether they want to keep their monuments and under what conditions they want to present those monuments. Unfortunately, that’s how this process started, and that’s part of what angered the people who chose to march. But more and more communities around the country will have to confront that legacy, and they’ll have to deal with the question of what to do with their memorials and with their monuments.

CoA: Reflecting on the events in Charlottesville and how the town will move forward, what do you think the Menlo community can learn from how your town dealt with the rallies, in case those protests come to the bay area?

Dean: So that’s a profound question, and I’m going to answer it very narrowly. One of the things Charlottesville has been looking at for a number of years is economic development and affordable housing in black communities. How to offer the black residents of the town the same sort of opportunities available to the white residents of the town, especially in the midst of a sea of gentrification, in money moving in places like New York, in Philadelphia, in Washington D.C. into Charlottesville.

People who are choosing Charlottesville’s retirement community for example, after living in one of those other areas, or people who are choosing it as a place to build their families, pushing blacks out of their historically black neighborhoods. Charlottesville has to answer those questions, they have to answer them quickly: How are we going to redevelop our community, in a way that is inclusive and ensures that these black families that have been here for a long time still feel welcome, and can survive, and can hopefully thrive in our community at large?

That’s not easy. It’s not easy to build affordable housing, and by the way, something that you might know about affordable housing, is that it moves in cycles that run counter to our intuition. It is much easier to build affordable housing when an economy is performing poorly than when an economy is performing well. Because when an economy is in recession, building supplies are cheaper, which allows you to offer those units of housing at lower cost to potential residents. So honestly, and I know this is going to sound a little sadistic and cynical but we’re waiting for another economic downturn to try make it cheaper for people to live there.

That’s also precisely the moment when they are likely to lose their job and their ability to pay. What does a community like Palo Alto or Menlo Park do? Doesn’t have the exact same history with race relations, but it does have some of the same problems with affordable housing and access to living wages, jobs in the community. You do see this in East Palo Alto, and there have been efforts by the East Palo Alto City Government to try and force companies, Amazon is an example, ongoing, to hire a certain number of workers out of local communities, to provide them with job training, to provide them with opportunities that ensure that once they take a job with Amazon, they can stay in East Palo Alto. That’s important. Be proactive, think about those underlying problems before you deal with the symbolic questions like what a monument might stand for.

CoA: There was a planned alt-right rally in San Francisco, and a huge outcry against it resulted in the location eventually being moved. Especially for such a liberal place for an alt-right rally to happen in San Francisco, do you see anything like that being scheduled near the Menlo community, considering there was one in Mountain View recently?

Dean: I do, absolutely, and you saw with the invitations to Milo Yiannopoulos and Ann Coulter to Berkeley last year, there is an effort to bring those provocative conservative figures to this area, precisely to challenge what seems to be the prevailing liberal elite ethos of this community and of surrounding communities. But I would just say this: free speech is free speech.

To go back to my prior point, communities have to be thoughtful about how they invite those individuals or how they confront the circumstances of an alt-right presence. But they need to honor the Constitution’s promise of free speech to all Americans, even if those messages can be hateful. Where they get to draw the line is when those groups threaten violence, and the Supreme Court has spoken pretty clearly about that limitation.