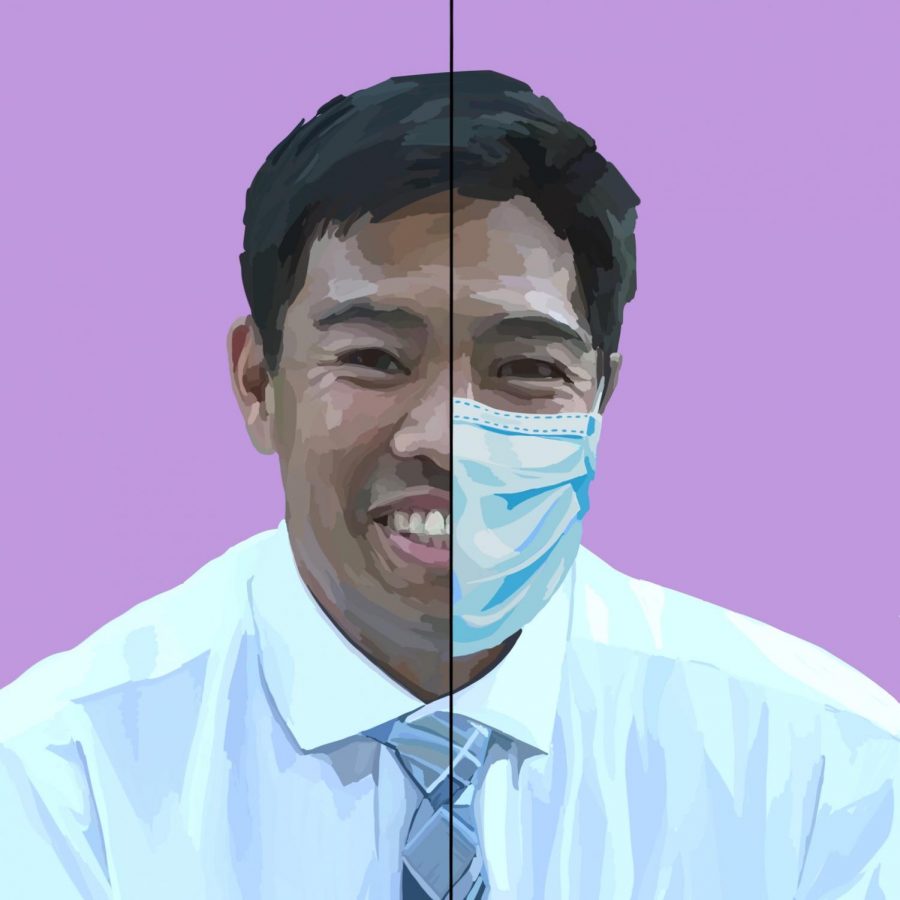

Behind the Mask: Dr. David Chang

A portrait of Dr. David Chang. The San Mateo County Public Health Department, where Chang is an assistant health officer, has been largely focusing on the impact that their decisions regarding the coronavirus pandemic have on at-risk health populations and health disparities. Staff illustration: Grace Tang.

June 8, 2020

Staff Illustration by Grace Tang.

Behind the Mask is a series exploring the lives of five medical professionals and how their lives have changed because of the coronavirus. This is part three of five, a profile on Dr. David Chang, assistant health officer at the San Mateo County Public Health Department and clinical assistant professor at Stanford.

———

Dr. David Chang never thought he would be where he is now. He started out his career as a journalist and then worked at a tech company. His interest in helping the underserved led him to work at an orphanage in Northeast China. Later, he returned to the U.S. and decided to attend medical school in hopes that he could do more work overseas. Eventually, he found himself in rural Virginia, where he became a health director and officer in an under-resourced area for six years.

Chang moved back to the Bay Area three years ago. “I was really interested in coming here, primarily so I could increase the relationships [between] Stanford and the community agencies around us,” he said. He also said he wanted to help develop bright students’ interest in public service. Now, he splits his time between working at Stanford as a clinical assistant professor and at the San Mateo County Public Health Department as an assistant health officer.

Chang said that it would have been hard for anyone to be fully prepared for the coronavirus. He said that the knowledge surrounding the coronavirus keeps changing. “It’s like drinking from a firehose,” he said. In public health, officials must consider the consequences that restrictive decisions could have. According to Chang, they try to make decisions very deliberately and do as little harm as possible, focusing significantly on the impact on at-risk populations and health disparities. “Not knowing what the right decision [was] gives everyone a lot of heartburn because if we make one decision it may help some folks, but it may result in harm [to] others,” he said.

According to Chang, the least restrictive actions in public health are the most ethical. “Asking a whole population to stay home: that’s just unprecedented,” he said. The coronavirus is also different from anything that Chang has experienced in his work in public health. “This is probably once in a lifetime for us. I’ve never seen public health have to issue these [kinds] of restrictive borders,” he said.

Chang talked about the negative ways in which shelter-in-place is affecting people, including depression and weight gain. “I think that every single person who’s in public health and who is issuing these orders to stay at home is aware of the behavioral and physical cost,” he said.

One reason for why preparing for the pandemic was difficult was that public health has not been properly funded to have the capacity for a workforce that is able to address a disease like the coronavirus, according to Chang. If appropriately funded, workers in public health departments could do more effective contact tracing and investigation. Chang mentioned efforts to pass legislation that would provide more funding for local health departments, allowing them to help contact and isolate people more effectively and to provide housing to people who have tested positive. “It’s very slow moving because the public health infrastructure here [in the U.S.] is not set up to do that,” he said.

Before the pandemic, Chang was working on projects related to addressing health disparities and the significance of social connections in health care; however, most of the work he now does in public health is related to the coronavirus. The San Mateo County Public Health Department is focusing on increasing testing availability to at-risk populations in nursing and assisted living facilities, jails, halfway homes and shelters.

Chang hopes that this pandemic gives public health officials the ability to deal with future health issues. “I hope coronavirus [makes public health] more visible and results in folks understanding how important public health is,” he said. He mentioned that funding tends to go in cycles when it comes to public health. For example, after the Ebola outbreak there was a lot of interest and, in turn, funding for public health. “When it’s not in the news anymore, a lot of the funding [goes] away,” Chang said.

Taking care of their four kids during shelter-in-place has been an adjustment for Chang and his wife. During his virtual interview with The Coat of Arms, he mentioned their daughter crying in the background, his wife helping their other daughter with homework in the other room, his son trying to read to his grandmother on the phone and another son on Zoom. “It’s been like every other household. We’ve had all this outpouring of support for first responders and medical staff, but I think the real heroes are the parents that are at home,” he laughed. However, he does worry about the impact that shelter-in-place and health restrictions will have on the well-being of children. “I feel really sad for my son and daughter, who previously swam four or five days a week and now can’t get in the pool. And my [other] daughter, who will never get to celebrate graduating fifth grade with her classmates,” he said.