Eating Disorders and the Menlo Community: Menlo Students Reflect on Eating Habits, Glorification of and Stigma around Eating Disorders

October 21, 2020

Note: This story is the second in a six-part package about eating disorders and the Menlo community. It was also originally intended to be in the October 2020 47.1 print edition of The Coat of Arms but did not print due to complications.

———

Eating disorders have long been an issue for the Menlo community. Despite a conversation being started by last year’s body positivity assembly, the stigma surrounding eating disorders at Menlo has remained present.

Since Victoria Garrick came to speak on her experiences with eating disorders in March 2020, the Body Positivity Alliance, also known as the BPA, has been formed by seniors Sabette Grieve, Izzy Hinshaw and Claire Ehrig. The BPA has made it their goal to continue the positive conversation sparked by Victoria Garrick’s speech. At Menlo specifically, the culture of eating has yet to be discussed in depth as a school wide issue. According to BPA leader Claire Ehrig, eating disorders have become a way to succeed socially, drawing up the connection between looks and popularity. “I think there is an association at Menlo of beauty being paired with wealth and status. The way you look is directly associated with your social standing,” Ehrig said.

Because of the competitive nature of eating disorders and their effects at Menlo, the environment only furthers the competition between peers. Menlo’s competitive environment and small size both contribute to an increasing pressure to be the “best.” “We’re constantly comparing ourselves to others. […] Menlo is filled with kids who want to be the best at everything. We want to look the best and dress the best,” Hinshaw said. According to Hinshaw, the concentration of students who want to outperform their peers contributes significantly to the pressures surrounding eating. She draws the connection between wanting to look the best and enforcing practices such as eating disorders to achieve those goals.

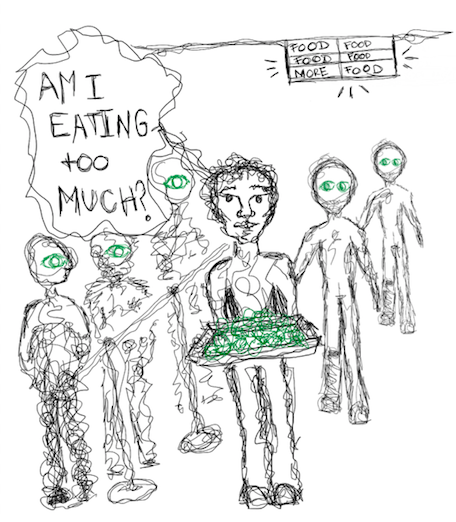

Furthermore, the cafeteria at Menlo has been known to be a source of stress and anxiety for students. As eating disorders are often displayed publicly by the amount of food one eats, the sense of competition is heightened at lunchtime. “I think there’s almost a sense of competition amidst the girls in the lunchroom for who can eat the least. Sometimes people will skip [lunch] completely and sit outside,” junior Charlie Herrin said. “There’s definitely a strong diet culture at Menlo, so much so that I’ve seen people avoid the cafeteria entirely to try and stay away from the toxicity of it all,” Herrin said.

The lack of food consumption increases the culture of eating disorders at Menlo and normalizes the destructive behavior that accompanies them. As well as validating the toxic disordered habits, it also creates a sense of shame for the students who do not have eating disorders. Disordered eating becomes glorified and is prioritized over eating balanced meals. According to Ehrig, the glorification of eating disorders harms everyone in its proximity to mealtimes. “[Problems with eating] are damaging both to the person currently struggling and to the people around them. People tend to judge themselves based on what other people are doing and say, ‘Should I be critical of my own body more?’” Ehrig said.

The subject of eating disorders at Menlo has gained traction in recent years but is still treated as an unimportant topic of discussion. Among peers, humor and insensitivity have both surfaced as results of the increasing discussion of the subject. According to junior Marshall Seligson, disordered eating habits have become more and more apparent. He points out the common example of only eating fruit for lunch as opposed to a balanced meal. “I’ve noticed that girls tend not to eat as much, especially when they’re at school with their friends,” Seligson said. He specifically singled out the term “grape-eaters,” which refers to the students who only eat fruit at the cafeteria. This term in particular highlights the stigma surrounding eating disorders and turns them into a joke of sorts.

Support for eating disorders has greatly increased over the past few years, but there is still a conversation to be furthered about ways to seek help. “Having an eating disorder and struggling with eating is one of the worst struggles one can have with mental health, in my opinion,” Ehrig said. According to Ehrig, Menlo’s social situation and current attitude towards eating disorders can be improved greatly. Furthermore, she stresses that more resources should be given to students. “I don’t think Menlo has done enough to educate people about the prevalence of eating disorders nor given us enough resources for how we should be keeping ourselves healthy,” Ehrig said.