Atlanta Spa Shootings Are A Consequence Of Anti-Asian Sentiments

June 4, 2021

On Tuesday, March 16, a white 22-year-old man shot and killed eight people at three different spas in the Atlanta area. Six of the victims were Asian women.

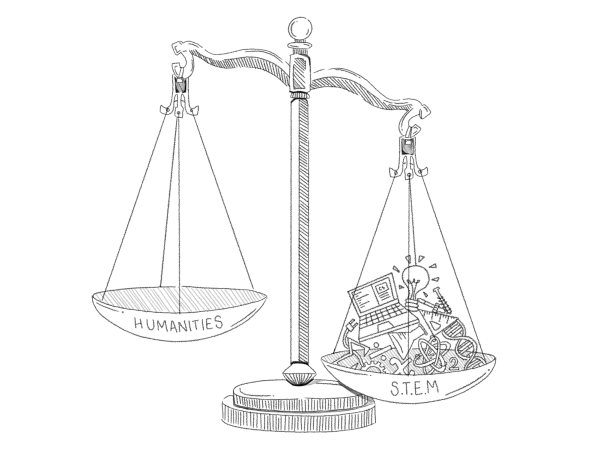

The shooter was an evangelical Christian and an active member of Crabapple First Baptist Church. Media outlets have rushed to either side of the political aisle, with left-leaning outlets recognizing potential anti-Asian bias and right-leaning ones emphasizing the shooter’s supposed sex addiction. However, both are missing the point — these attacks are not simply identical to other anti-Asian attacks that have permeated the news, and they certainly cannot be excused by a “sex addiction”.

“The suspect told the police that he had a ‘sexual addiction’ and had carried out the shootings at the massage parlors to eliminate his ‘temptation,’” according to the New York Times. However, psychiatrists have contested the validity of sex addictions. “Despite social acceptance of the term — and the pattern of killers claiming it as a motive for their crimes — sex addiction isn’t an accepted psychiatric diagnosis,” according to CNN. Researchers have not observed neurobiological evidence of addiction like they have with substances such as drugs or alcohol, and sex addiction has been rejected from the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

Evangelicalism and supposed sex addiction are also inextricably linked — abstinence and sexual control is encouraged by a slew of Christian sex addiction support groups. The first such group, Sex and Love Addicts Anonymous, was founded in 1977 by an Alcoholics Anonymous member and is based on a similar model. In the Evangelical Church, sex and alcohol addictions have been historically deemed synonymous. “Men who identify as evangelical Christians […] are a third more likely to say that they’re addicted to porn,” according to Time Magazine. These men are likely to believe that normal sexual urges are sinful or deserving of correction. Purity culture creates a fear of sex and sexual feelings while simultaneously blaming women for “causing” male impurity. Men are deemed inherently hypersexual, while the culture teaches that women must prevent the temptation of this sexuality, according to Religion Dispatches. This ideology only worsens when combined with the historic fetishization of Asian women.

The intersection of race and gender for Asian women results in degradation on the basis of both separate parts of their identities, but also a combination of the two. Congress supposedly enacted the Page Act of 1875 to curb the immigration of prostitutes to the United States. However, this was a veiled institution of anti-Asian sentiment: the government used it to systematically bar entry to the country for Asian women. U.S. military members also have a history with the prostitution of Asian women, including World War II and the Vietnam War. Popular culture and media reinforced these stereotypes of Asian women as docile sexual servants. The phrase “me love you long time” originates from Stanley Kubrick’s 1987 movie “Full Metal Jacket,” where a Vietnamese woman uses it in an attempt to seduce two American GIs. According to AsAmNews, Americans now use the pervasive phrase to refer to Asian women and sex, and it has been reinforced far past its original coinage.

The Atlanta shootings were not simply another of the myriad anti-Asian attacks that have overrun the news. Rather, they are a tangible effect of the intersection between White supremacism and evangelicalism, race and gender. Xenophobia reinvigorated by COVID-19 and prominent politicians’ use of phrases such as “Chinese virus” has undoubtedly contributed to racism towards Asians. However, we cannot ignore the specific historical context for Asian women. Only then can we achieve justice for the women who have been treated so poorly by the media, government and people of the country they call home. “I just want to hold her tight,” Jamie Webb, the daughter of Xiaojie Tan, one of the victims of the shooting said. “Give her a hug… hold her hand, hug her for a long time.”