Menlo Should Minimize “Push Weeks” to Alleviate Students’ Stress

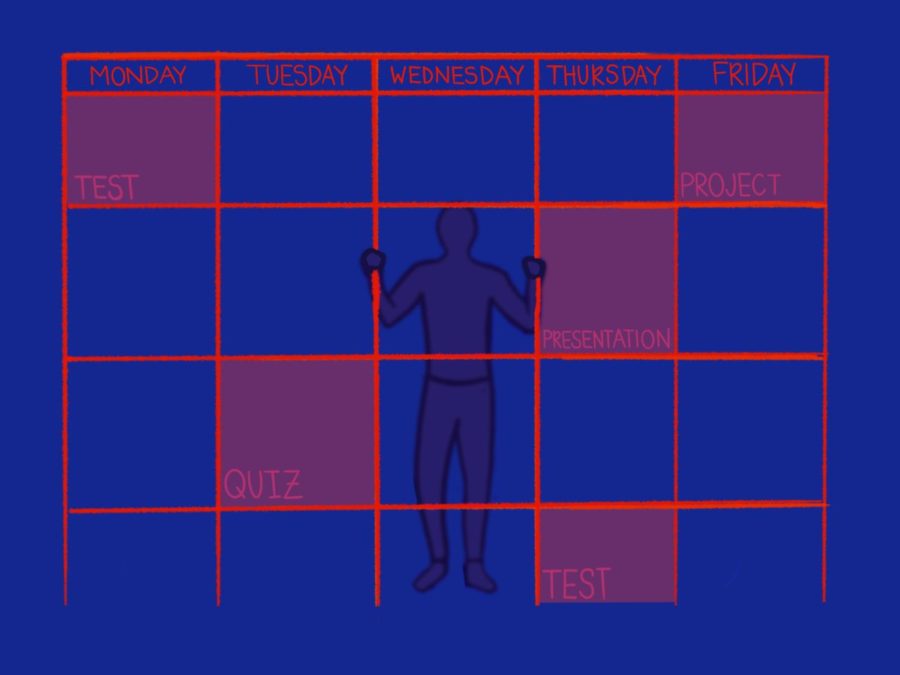

Push weeks come in 2-3 week cycles, where students have weeks with little work and then weeks with an overload of work. These push weeks increase students’ stress levels and workload at the end of each cycle, due to similar unit lengths across multiple departments. Staff illustration: Sophie Fang.

December 9, 2021

We’ve all had those weeks. 5-6 hours of homework each night. One test on Monday, two on Wednesday and another on Friday. No time to sleep, eat, exercise or relax. And if you miss a day or even a class period, catching up is impossible because there’s just too much work.

Some students have dubbed these weeks as “push weeks” because that’s how they make students feel — like they’re pushing and pushing and pushing until the week is finally over.

An example of a recent push week was the week before Thanksgiving break. In addition to a regular homework load, I had two projects due on Friday and three tests, all for different classes. What was perhaps the most frustrating part about this experience was the taunt of Thanksgiving break. I knew that I’d have the next week off, but I had to submit assignments the day before we were let out for break, exponentially increasing my stress.

Another thing that adds to the stress of push weeks is how they tend to come in cycles. Students have two-to-three weeks of no tests or major projects due, and then one completely hands-on week where students have tests and projects due almost daily. In my experience, these tend to come right before breaks, like Spring Break, which is not necessarily unexpected because teachers want to wrap up their units before break. The fact that push weeks are in cycles contribute to the stressful effect they have on students. At least one week a month, students have more work and get less sleep than if the work was spread more evenly across the month.

Push weeks are a consequence of having little communication across departments, leading to an accumulation of assessments in similar time periods. “[In department chair meetings] we have talked about the fact that there is a kind of a cyclical nature to how units work. But we haven’t talked about solutions to this specific concern,” Science Department Chair James Formato said.

This lack of communication is something that impacts teachers as well, who strive for methods to discuss with teachers from other departments. Math teacher and Dean of Student Life Programs Eve Kulbieda acknowledged that while there is some communication between departments for interdisciplinary purposes, such as physics formulas being applied in math class for freshmen, there are no formal ways for teachers to communicate with one another in terms of unit length. “We’re hoping for some communication method, ” Kulbieda said.

However, Kulbieda believes that a shared assessment calendar could negatively impact teachers as it will decrease the flexibility they have to accommodate student needs. Essentially, a shared assessment calendar would entail creating a calendar with mandated assessment dates spread out over a period of time that teachers would be unable to change. “Some teachers want to be responsive to their students and move an assessment date because the students aren’t ready to assess. [An assessment calendar] might disadvantage them,” Kulbieda said.

Despite Kulbeida’s concern about assessment calendars, it’s apparent that push weeks have overwhelmingly harmful repercussions for students, meaning the school must prioritize student wellbeing over any disadvantages assessment calendars may have for limiting teachers’ responsiveness. Creating an assessment calendar should be made more of a priority because push weeks negatively affect a wide percentage of the Menlo community.

Frustratingly, the administration has not prioritized a solution for push weeks. According to Kulbieda, who is also the leader of the Academic Committee of the student council, and senior Ashley Grady, who is a member of the Academic Committee, there has been discussion among the administration and student council about reaching a solution for push weeks. Even so, these discussions have not led to a solution, as members believe that there is no easy solution. “I think if we can do something to address it, that would be great, but at the moment that’s not what we’re focusing on,” Grady said.

However, the administration has still made a commendable effort to limit stress for students near exam time, which is something that I (and I’m sure many others) appreciate. For example, at the end of last year, Upper School Director John Schafer and the student council mandated blackout days, when testing is prohibited, near final exams during November and December. “We are always in conversation about helping students manage their workload and manage their stress levels,” Formato said.

It’s clear that the goals of students, teachers, departments and the administration are aligned: limiting stress as much as possible for every member of the Menlo community. Fixing and prioritizing push weeks would fulfill that goal.

Having meetings with multiple departments about test schedules and unit lengths with the goal of creating a basic outline for a master assessment calendar will help alleviate students’ stress, contributing to their mental health and wellbeing, while also simultaneously diminishing the repercussions of push weeks. Another possible solution is blackout weeks for certain subjects. For example, English and History classes could be allowed to test the first week of the month, and Science and Math classes the next week. By doing this, testing would be spread out more evenly across the month. Student input is an important step of the process of reaching a solution for push weeks — the administration should also reach out to students about this issue to hear their concerns or commentary.