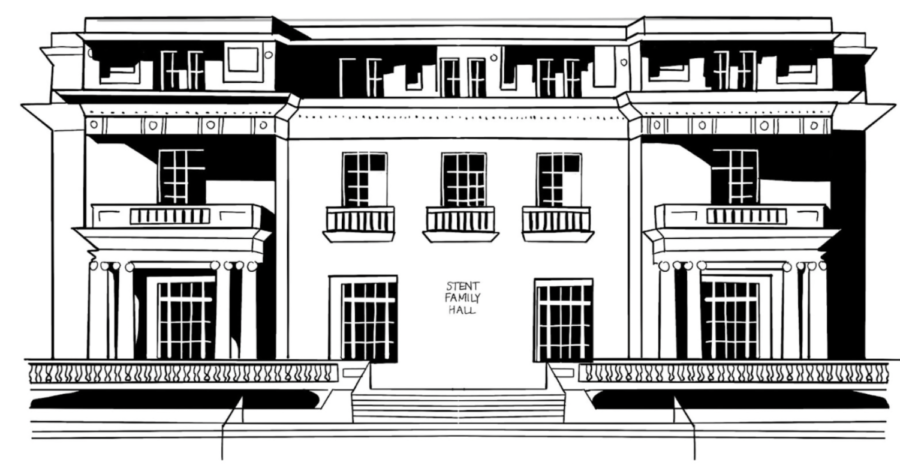

The massive white mansion at the head of the loop draws the attention of students, parents, faculty and visitors alike. Today, the towering building is known as Stent Hall, but many fail to acknowledge the decades of tradition and meaning that it carries.

Through the years of serving as Menlo’s edifice, Stent Hall has undergone a multitude of tribulations and changes. The current library, offices, student center and cafeteria that connect to its structure weren’t always there.

Douglass Hall

In June of 1921, Leon Douglass purchased the Theodore Payne house for his family; at the time, Menlo was a small all-boys school transitioning from a foundation of military instruction to an educational foundation.

Two decades later, in 1945, the Douglass estate was sold to Menlo School and converted from a manor to a building better suited for a school. While originally named the Victoria Manor, after Douglass’ wife, the building became known as Douglass Hall for generations as a cornerstone of Menlo.

1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake – Closure and Restoration

On Oct. 17, 1989, the Loma Prieta earthquake sent shock waves throughout California. According to Menlo history teacher Charles Hanson, the 6.9 magnitude tremor was strong enough to splash swimmers out of their residence’s pool in Los Altos Hills just several miles south of Menlo Park — its effects were felt in many ways throughout the state.

Among the thousands of buildings damaged in the earthquake was Douglass Hall.

The book “Celebrating 100 Years” by Hanson states that the building’s foundation was cracked as a result of the earthquake. Leaving Douglass Hall untouched in its state of disrepair was dangerous, and this led to debates about what to do with the hazardous mansion.

“The sort of ruthless and efficient thing to do is to [tear it down],” Hanson said. “Which is just terrible, but, as they say, ‘if [there’s a] burning house, do you run in just to run out?’ Douglass Hall wasn’t a burning house, but it was a damaged one.”

The same group in favor of the building’s destruction also reasoned that an estimated cost of $7 million to repair and renovate the structure would be better served to build a completely new one more fitting of a modern-day school.

With neither group satisfied with the decision made by the Board of Trustees, the historic mansion at the forefront of Menlo’s campus was temporarily closed with seemingly irreparable damage. The building’s inactivity would last for almost a decade.

During its closure, two main groups emerged as supporters for the preservation of the historic edifice. The first was a collection of people who called themselves the “Friends of Douglass Hall.” The other was a group of three women serving on the Board – Fran Arrillaga, Margaret Beltramo, and Mary White – dubbed “The Iron Ladies.”

Together, the two small organizations worked tirelessly to attempt a reopening. Douglass Hall would require reinforcement with heavy iron around the building to support it, but an unfortunate obstacle would nearly hinder the plan completely. According to the previous Head of School Norman Colb, three women snuck into the building one night while it was closed, getting past a security fence around the perimeter. They were subsequently arrested on the roof without harm, but the event held a larger implication. There was a danger to the women from the unstable structure of the building, and had any of them been injured, Menlo would’ve been under significant legal pressure. “School could’ve been closed [permanently] because insurance would’ve been extremely difficult [to handle],” Colb said.

The eventual solution to Douglass Hall’s precarious situation was to buttress the building on three sides – a library and student center were established in a new wing to support the hall. Around twenty percent of the original building was demolished to allow for the new, stronger structure, but a majority of the historic features remained. As stated by Chief Financial Officer Bill Silver, the work cost Menlo approximately $11.5 million to complete.

After years of arguments and the threat of lawsuits, Douglass Hall finally reopened in September 1998 anew. However, it would bear the new name of Stent Hall. Colb suggested to the Board that the school rename the hall in honor of Peter Stent, the first Chairman of the School Board, for his steadfast efforts to get the building funded and reopened. “His very protracted work on getting that done, on getting those decisions made, entitled him to having the building named after him,” Colb said.

Modern-Day Stent Hall

Menlo made several more changes to the building to create the Stent Hall that exists today. Menlo spent $20.7 million to establish the dining hall and put into place the business, communications and development offices on the third floor. While perhaps not the same antiquated and classical house it once was, present-day Stent Hall combines the historical significance of the building with modern and practical functionality for students and faculty.

Associate Director of Admissions Janet Tennyson appreciates the steady presence of the building over the years. Having been at Menlo since Stent Hall’s reopening in 1998, she’s seen it evolve over the years but hold the same powerful presence. “Stent Hall has been a constant for many of us who have seen so many changes take place on campus over the years: the change in our physical campus appearance, with so many new buildings popping up, the change in our student body, as new students enter and graduating students depart for the next chapter in their lives, the change in personnel who give their heart and soul to the school then move on to new ventures,” Tennyson said. “It’s the building that houses many memories of the hundreds of people in our community who have made Menlo what it is today.”

The Future of the Mansion

Hanson believes that paying respect to buildings such as Stent Hall — or historic facets of nature such as the trees on the middle school campus — is critical in respecting Menlo’s locality. However, he admits that might be difficult in the future.

“[Stent Hall] is an icon like the trees on the middle school campus, but we’ve got the same problem right now with the Oaks,” Hanson said.

Menlo has lost two beloved oak trees in the 2022-23 school year, the second due to heavy rain and high winds in the bay area. “On one hand, they’re dangerous. Do you take them all down and lose that visual icon?” Hanson said.

The question he poses is one Menlo might have to grapple with in the coming years: what compromises must be made in order to ensure the safety of the community while attempting to keep the iconicity of Menlo’s campus?

“These problems are not going away, especially with climate change. There are going to be more problems with big old trees. There are going to be more earthquakes here,” Hanson added.

But for now, Stent Hall and other historic parts of Menlo’s campus will stay standing, keeping Menlo’s rich history of both tradition and innovation alive.