When the Menlo “Weekly Announcements” email rolls in every Sunday, I’m almost always looking forward to seeing what exciting events and news the upcoming days will bring. However, when I notice that a blackout week is looming on the horizon, I can’t help but heave a resigned sigh. This may sound counterintuitive — why wouldn’t I rejoice at the opportunity to set the computer and textbooks down? The reality is that, when executed poorly, blackout days can cause more harm than good.

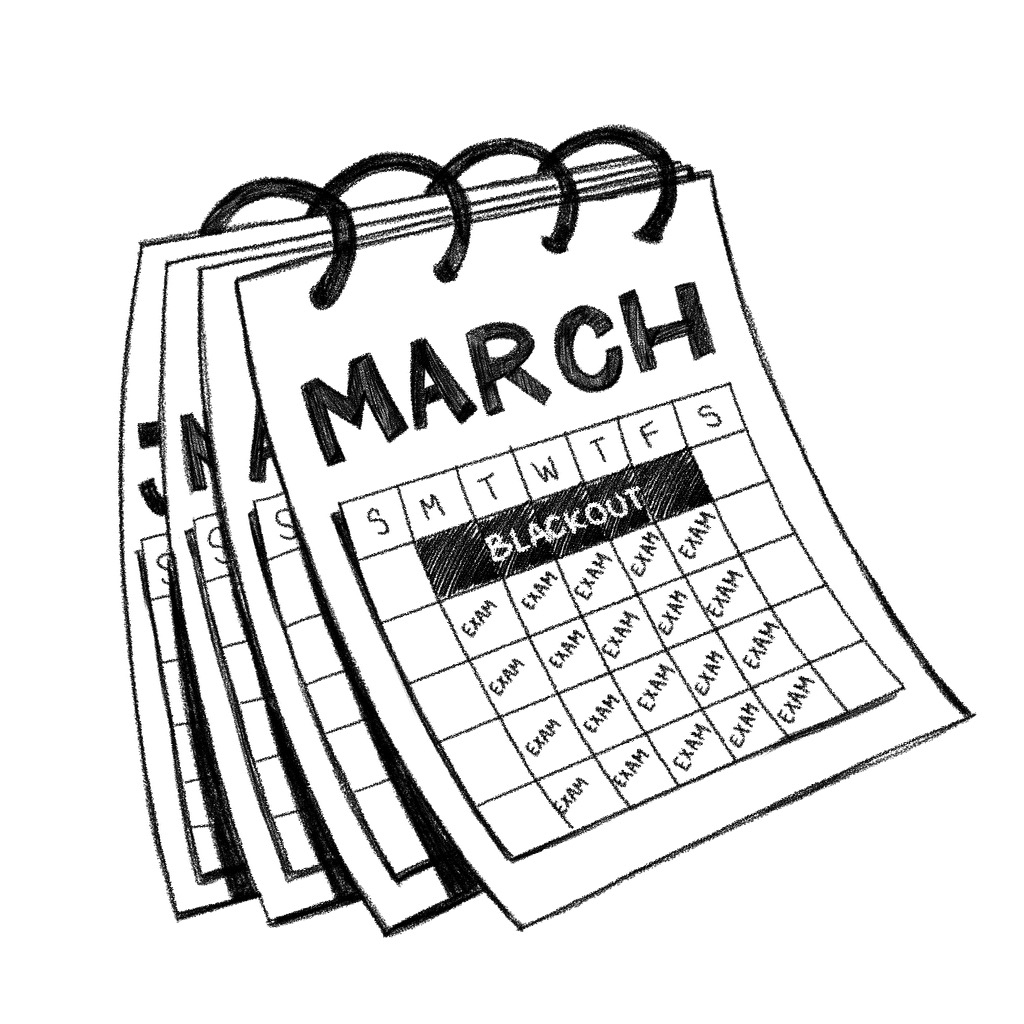

In a Menlo setting, a blackout week designates a period of time during which teachers are prohibited from giving unit tests or large assessments. In theory, blackout weeks are implemented to reduce stress levels among students and prevent academic burnout. By having tests staggered and spread out, students are allowed more breathing room and time to study.

Hypothetically, blackout periods sound like a wonderful idea. You’re saying spread-out tests and more time in between to prepare? Sign me up! In reality, though, I’ve found that blackout weeks often condense assessments into a shorter, more demanding time, inducing worry and mental exhaustion among students.

First, rather than relieving students’ stress, blackout weeks frequently cause assessments and projects to cluster and coincide with one another, immediately before and after these designated blackout periods. As a result, students often find themselves juggling a flurry of stressful tasks and assignments in a short timeframe, completely defeating the purpose of the blackout week system. Consequently, students are attacked by a whirlwind of academic pressure and anxiety; considering how ordinarily stressful high school can be, blackout weeks can actually have a negative influence on a student’s wellness.

Additionally, blackout weeks may give students and teachers alike a false sense of security. Teachers assign larger, long-term projects beginning before and ending after blackout weeks. In doing this, teachers may assume that students will have extra time to complete tasks during blackout periods and expect them to complete extra work during that time.

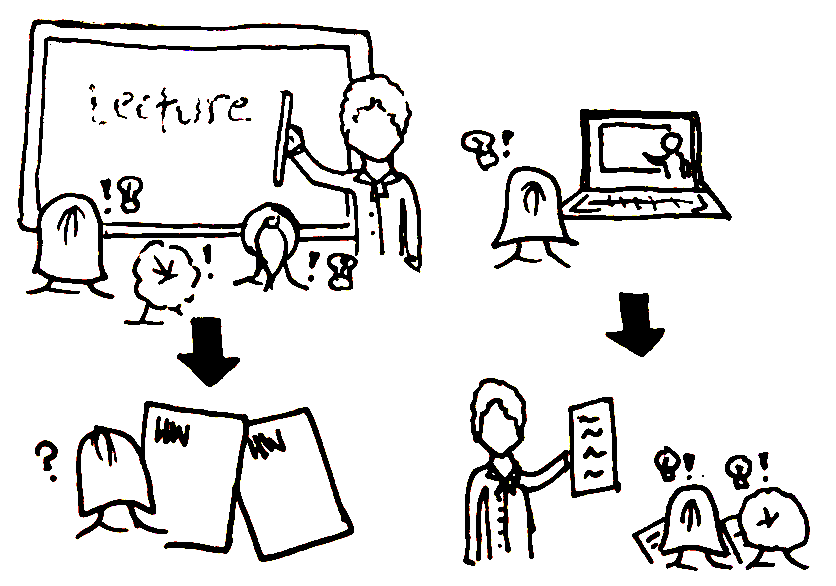

I’ve noticed that it can sometimes be difficult for teachers to sync their lesson plans and curriculum in a balanced manner with one another. In many of my classes, we begin and finish units in tandem — this is understandable, as I know that there is an ideal unit length that many teachers like to aim for.

However, for other students and myself, having many projects and assessments inherently line up can exacerbate the negative effects of blackout weeks. Teachers only have a few days to wrap up lessons and cram in exams before the blackout hits; and when all classes finish their units at the same time, these two factors together provoke a barrage of stressful tests and studying. Even if unintended, tension and pressure is at a high during blackouts and the days around it.

Am I saying that increased academic stress during blackout periods is the result of Menlo teachers’ actions? Not at all. All I mean is that blackout weeks can be inherently flawed. Though the idea of alleviating student stress is positive, there must be a better way to do so.

I would propose that teachers find a way to sync their curriculums and plan around one another. I understand that teachers can be incredibly busy and that syncing assessments is not an easy task. I also acknowledge that this will take a fair amount of work from the teachers’ end; however, that work would be seriously appreciated. This possible solution can mitigate confusion and stress for both themselves and their students. Then, everyone can have peace of mind, knowing that students won’t have three tests in a day or that the optimal time to schedule the unit test is on Tuesday.