When teachers are not grading papers, lecturing or writing assessments, a few can occasionally be found strategically negotiating in the board game Diplomacy. While many of these teachers no longer consider themselves regular players, they still reminisce about the game and its rewards, found in its blend of strategic thinking, negotiation and thrill.

Diplomacy is a board game where each player represents a different country in Western Europe before World War I. Players start with a certain number of supply centers depending on their country, with the goal of obtaining the majority of the supply centers. Negotiating with other countries, forming alliances and eventually backstabbing one’s closest allies are key strategic components of the game. Players write “secret” instructions for each supply center, choosing if they would like to attack another country, defend their territory or support their or another player’s attack. A game can last up to months or even years.

History teacher Charles Hanson first discovered the strategic board game as a high school student. His older brother played different war games, such as the popular game Risk, and encouraged him and his friends to try Diplomacy. “My friends and I really, really enjoyed it, but then it just faded out of my life until I got here to Menlo and someone turned me on to the online version,” he said.

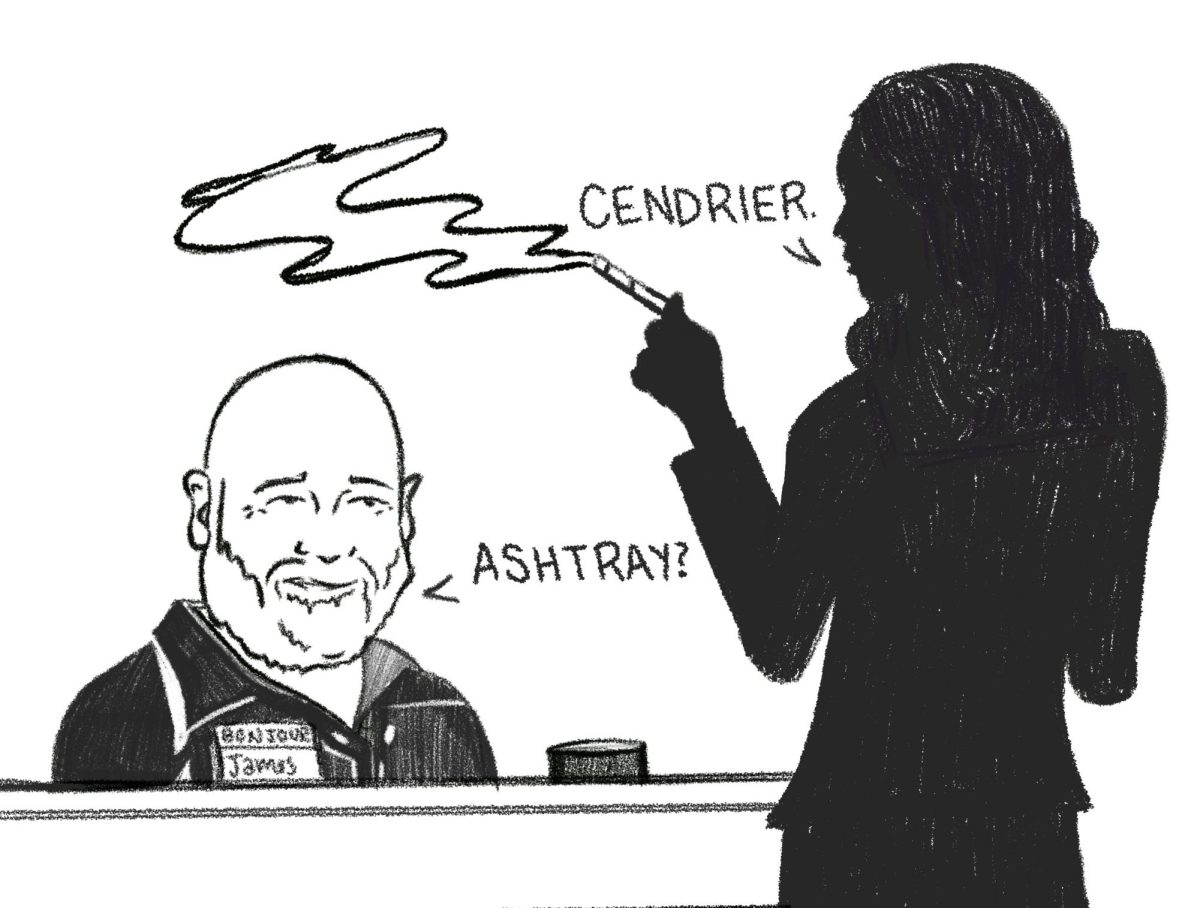

Since then, Hanson has inspired his colleagues to play the game as well. Applied Science and Engineering Teacher James Dann credits Hanson for his introduction to Diplomacy around 20 years ago, during his first year teaching at Menlo. Dann played Diplomacy regularly in the years following this introduction, including a heated student-teacher game. “We had a teacher game, a bunch of us, a full-day game that was pretty fun, except Charles Hanson stabbed Mr. Henry Klee’s son in the back, and that was problematic,” he said. “Charles Hanson looks like a nice guy, [but] he will stab you in the back in a second.”

All rivalry set aside, Hanson and Dann taught a week-long mini-course on Diplomacy over a decade ago through “Knight School,” a week of mini-courses later replaced by M-Term. “When [Dann] saw that I was offering a class on Diplomacy, he said, ‘Oh, I play Diplomacy. Let’s do it.’ And I did that for several years,” Hanson said.

When Knight School was discontinued, Hanson created the United States Foreign Policy class and began to incorporate a game of Diplomacy into the curriculum. “It is the best way I have come across to simulate negotiation. Diplomacy, after all, is the alternative to force,” Hanson said. “It’s catnip to a lot of adolescents. They haven’t played anything quite like it before.”

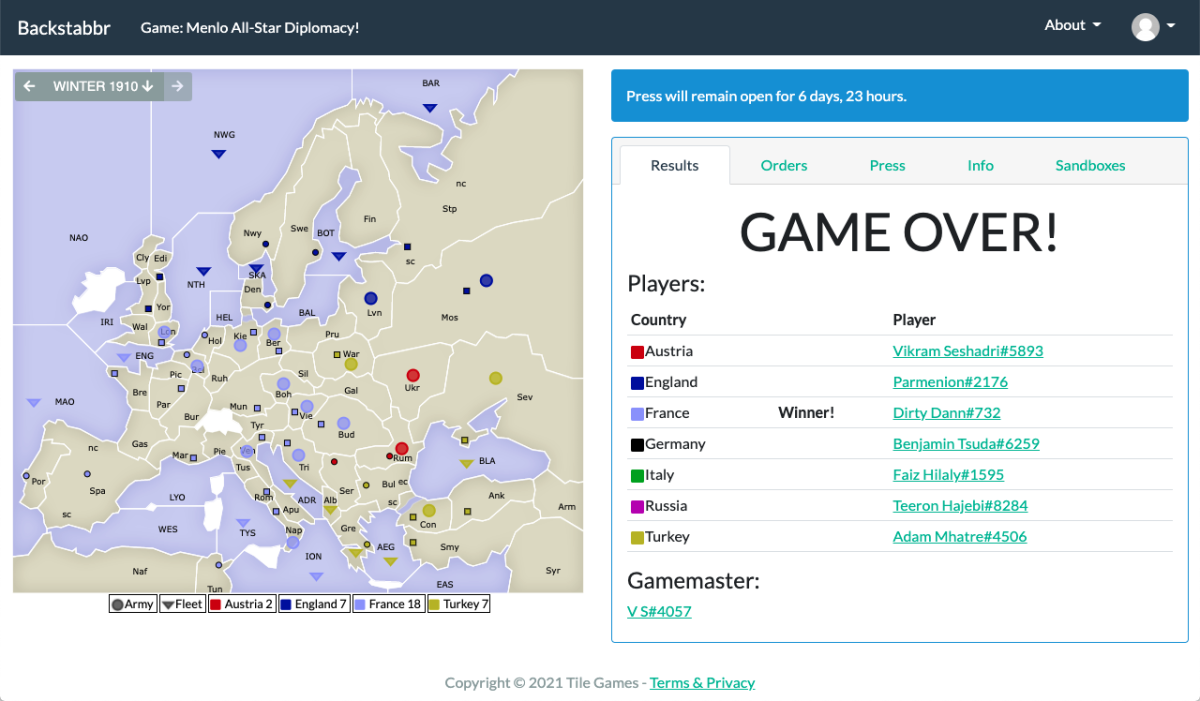

To Hanson, the lack of chance sets the game apart, as there are no dice. “You can’t blame your luck,” he said. “There’s something psychologically satisfying to a lot of people that the chance element has been taken out.” Some of the students in his foreign policy class enjoyed the game so much that they decided to continue playing using the online version “Backstabbr” even after the semester ended.

Upper School Director John Schafer, who used to play Diplomacy with his friends in high school and college, does not regularly play the game anymore but still appreciates the thoughtfulness behind the game. Because players have to form alliances and build trust while also avoiding getting backstabbed, Schafer believes the game teaches essential life lessons about navigating competition. “Sometimes you’re going to turn on people. Sometimes they’re gonna turn on you,” he said. “You have to make good alliances that you can count on.”

Upper School Science teacher David Spence has been playing Diplomacy for 30 years and still plays around twice a year. He played alongside Dann, Hanson, and former math teacher Henry Klee. While it’s been over two years since the group got together, Spence misses their light hearted Diplomacy games. “We should actually start a new game,” he said.

In particular, Spence finds the game exciting because players must backstab their closest allies to win. “People are talking behind your back. You’re talking behind their back. You’re making alliances. You’re breaking alliances,” he said. Spence has learned more about his colleague’s personalities through their negotiations.

Because all the teachers in this group appreciate history, it adds an intriguing element to the game. The game takes place during World War I, and players sometimes feel as if they are reenacting the war. “I love how it deepens your understanding of history,” Dann said. “You see why things happen the way they did in World War I. You really see it has to do with the country’s strengths and the geography.”

Dann describes the game as highly intellectual and is fascinated by the multifaceted aspects, especially the counterplay of trust and deceit. “You feel like [the] Secretary of Defense or something. It’s amazing the number of possibilities for each turn, and there’s always some risk involved,” he said. “It’s the most interesting board game I’ve ever played in my life.”

In the future, Dann hopes to join his colleagues again in a friendly game of Diplomacy. “We should [play Diplomacy] for Professional Development Day,” he said.