Why the History Honors Policy was Redacted

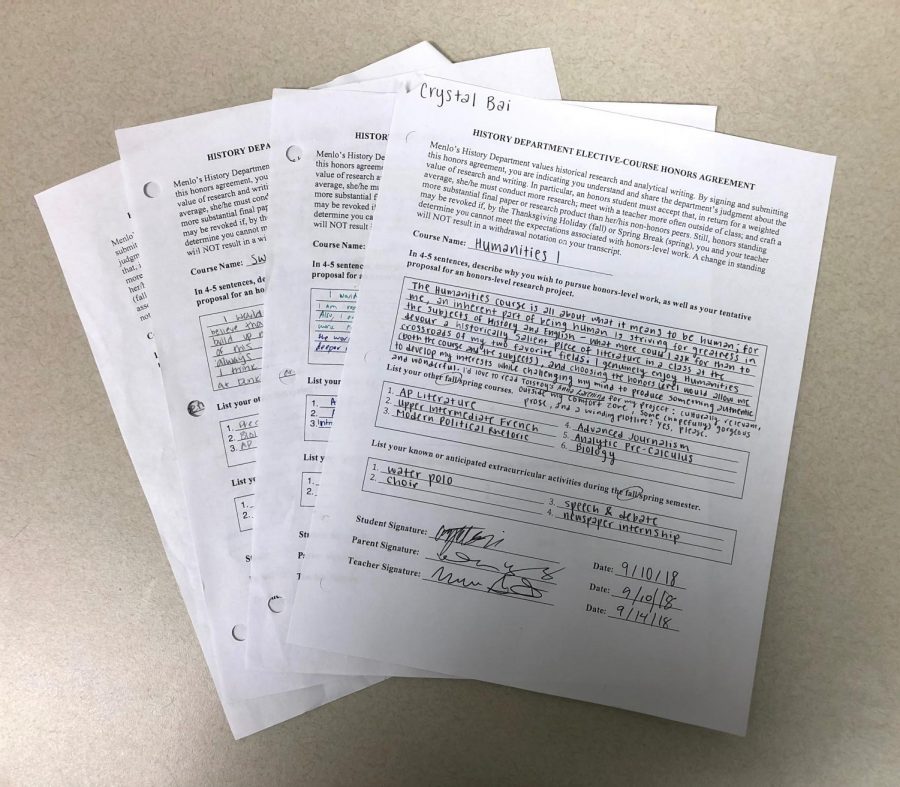

Image of the history elective-course honors agreements students were required to complete. Staff photo: Crystal Bai

September 24, 2018

As of this school year, the history curriculum has officially changed, making AP U.S. History a sophomore class and introducing 19 electives for juniors and seniors to choose from. Except for the classes AP Government and AP Economics, each elective now offers an honors option for students who wish to pursue honors-level work.

Because history honors classes have never been offered before, the history department had to decide the specific nuances surrounding the honors track. Students may have heard different iterations of what the history honors policy actually is.

According to History Department Chair Ryan Dean, the policy has now been suspended, but previously involved two parts. “First, the department wanted to offer every student in all of our non-AP junior and senior elective courses an opportunity to take one elective per semester with an honors designation,” Dean said. “Second, the department wanted to limit students to one honors option per semester. The rule applied only to honors classes. Students in an AP history course could simultaneously take a non-AP elective in an honors capacity.”

The history department is currently the only department at Menlo that does not restrict students access to honors coursework, which Dean believes is an inclusive approach to course placement consistent with the values of the school. However, after considering a variety of alumni survey data presented to all Upper School teachers over the past several years that suggested Menlo’s academic program may be too rigorous, the administration began to look for ways to dial down student stress and peer-to-peer competition.

“The [previous] cap on the number of [history honors] classes emerged in response to a deeply-held departmental belief that research-based analytical writing is hard, so it would therefore be a mistake to allow students to engage in two [final] research projects simultaneously,” Dean said. “While the History Department empathizes with passionate students who want to undertake multiple research-based history courses at the same time, we also believe our cap rule responded to Menlo’s stated interest in helping students enjoy balance at school.”

The history honors policy was redacted because of backlash from the student body, according to Upper School Director John Schafer. “As the story got told to the student body, students viewed it as an unfair disadvantage and another example of prioritizing STEM over humanities,” Schafer said. “So, I said: ‘Look, let’s back off a little bit and not get into that fight with students.’ If there are students who are dying to take two honors classes, let’s deal with them on a case-by-case basis.”

While the history honors cap is no longer effective, Schafer hopes to create a broader policy through the entire Upper School that decreases academic stress. “The upshot of [the alumni survey data] is that [Menlo] does a very good job of preparing students for college, but the experience they have here is more stressful than we would like to be,” he said. “There’s more competition than anyone would like there to be, which raises the question: what can we do about that? Ideas include restrictions on taking seven academic classes or limiting the number of AP and honors classes a student takes over [the course of] their high school career.”