Do Later Blocks of the Same Class Have Higher Test Averages?

February 14, 2019

The issue of whether or not the average grades for students in the later block of the same class are higher than that of students in the first block of the class, due to students giving each other hints about what is going to be on assessments, lacks concrete evidence. However, the ethics surrounding where to draw the line for cheating is unambiguous for Menlo teachers.

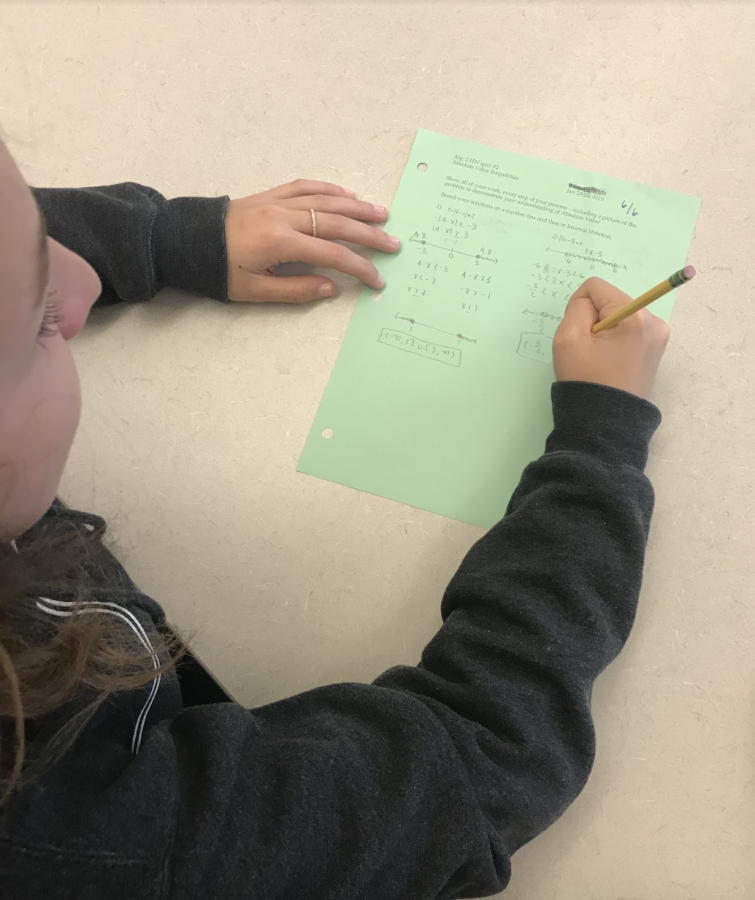

Students tend to hold the belief that despite giving out hints to others, the discrepancy in grades is insignificant. “On quizzes it’s fairly easy to cheat, but on tests, you have to know the material in a lot more depth, so I don’t think that the difference is very significant,” sophomore Siena Gavin said.

Students are aware that oftentimes information is shared with one another, but they are very clear about where to draw the line between cheating and just talking. “Honestly I don’t think that [talking about assessments] is that bad, because I don’t feel like students are crossing the line that much in my experience,” Sophomore Mallika Tatavarti said. “Personally, I think it’s fine if students are just talking about the level of difficulty of the test, but you have to draw the line when students are giving out answers to test questions.”

Data from math teacher Eve Kulbieda’s freshman classes corroborates this claim. Kulbieda has three blocks of the same class and over the course of the four tests that have been administered this year, no notable patterns emerged. For one test, the first block had an 89% average, whereas the last block had a 97% average; however, for another test, the first block had a 91% average and the last block had an 85% average.

“My dream is that they don’t [share information]. And I put a lot of trust in my students that they behave with integrity,” Kulbieda said. “I tell my students that they shouldn’t speak about it at all and if I hear them speaking about it or in a group speaking about it, then I would assume cheating. And then that would result in some disciplinary action.”

Menlo’s mission statement echoes Kulbieda’s view on integrity, as it states that students are expected to “demonstrate courage, integrity and a commitment to ethical behavior.”

Moreover, math teacher Rebecca Akers is unsure of the true extent of which hints influence the overall class average. “I do know that students do talk to one another during the day. And it’s not that they are intentionally planning to cheat or convey information, I think it’s just natural to talk,” Akers said. “But, different sections are composed of students with differing abilities, so you cannot necessarily assume that differences in performance are due to some students having advance information about the test.”

Science teacher Eugenia McCauley echoes this claim. “Since I have not seen a huge discrepancy, I don’t think it’s a huge deal in terms of how much it actually affects grades, but my guess is that it happens a lot and it shouldn’t,” McCauley said.

Even though it is unlikely that students giving hints out to one another affects a students’ grade, the prevailing belief from students and teachers is that giving hints is unethical.