Eating Disorders and the Menlo Community: French Teacher Corinne Chung Shares Her Experience With Eating Disorders

October 21, 2020

Note: This story is the fourth in a six-part package about eating disorders and the Menlo community. It also appeared in the October 2020 47.1 print edition of The Coat of Arms.

———

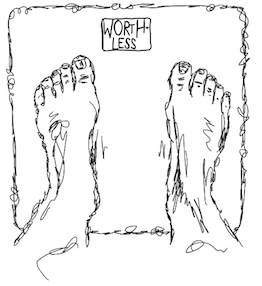

When she was 16, Corinne Chung developed an eating disorder. Living in Belgium at the time, Chung was living in a time period much different from our current one, with significantly less research and help available. The Upper School French teacher said she started out by starving herself, a symptomatic anorexic behavior. “So I lost tons of weight,” Chung said. But when her family intervened and pressured her to eat, she switched to purging behaviors more associated with bulimia. “I switched to bulimia because [my family] forced me to eat,” Chung said.

Chung explains that her eating disorder wasn’t centered around feeling beautiful, rather around having control of her body. She admits that during a time of stress and anxiety, it was a sort of coping mechanism for her problems. “It was an unhealthy way for me to control my emotions and deal with stress,” Chung said. She also explains that her doctors had no perception of the severity of her eating disorders. Rather than treating her eating disorder as a mental ailment, they focused solely on her inability to eat. “They felt I wanted to look good and skinny like [models] in magazines. The doctor didn’t know exactly how to treat it, so he told my parents to sit me down and force me to eat,” Chung said.

Chung’s familial relationships were greatly affected by her experiences with eating disorders, specifically with her mother. “I got very unhappy with my parents, [especially with my mom] because she didn’t want to recognize that I had a problem,” Chung said. Chung admitted that due to her mother’s perfectionist tendencies, it became a very stressful home environment. “I felt I had to be the girl [my mother] wanted me to be and that meant not being myself. I felt I had to satisfy her in every way. I was afraid of disappointing her,” Chung said. Furthermore, Chung revealed that pressure from her family was a factor in her decision to move to the United States. “I felt like for me to survive, I had to run away,” Chung said. For Chung, the best way to keep herself healthy was to surround herself with people who supported her. She felt that moving was necessary in order to get proper treatment and support because her family was furthering her anxiety and stress.

But despite having been urged out of anorexia, Chung explains that she found other ways to control herself. “I wasn’t cured. I was in a state of depression,” Chung said. With her increased stress and anxiety, Chung admitted that she needed to find other ways to cope than by not eating. “I didn’t know how to deal with everything, so I ate and threw up,” Chung said.

During her time in high school, Chung recalled a certain stigma surrounding eating disorders that made her feel ashamed. “I was completely alone and isolated. I also heard people making fun of [eating disorders.] People would say ‘Those girls have nothing to do but to stop eating.’ So, I hid it because I had heard so many negative comments about it.” This stigma increased her anxiety surrounding the matter and made Chung’s mental health decline even further. She explained that it was a completely different time and that people did not respond well to eating disorders. “People don’t know how to deal with you. They don’t understand what’s going on.”

Furthermore, Chung’s academic and social life were swayed tremendously by her eating disorder. “Because I didn’t eat enough, I couldn’t go to school for a while. I lost almost all of my friends,” Chung said.

For many years following her high school experiences, Chung said she remained bulimic for at least 15 years before seeking help. She explained that eating disorders affect people of all ages, not just teenage girls. “People don’t realize that it isn’t just a teenager problem. Some young adults develop eating disorders, and some of them [last] until much later in life,” Chung said.

However, Chung has been in recovery for many years now and is able to recount her experiences. “I think you are always in recovery.” She compares her attachment to her eating disorders to an alcoholic’s attachment to alcohol. She explains that she will always have an addiction to restricting her eating. She also admits that while she is grateful not to have life threatening damage done to her body, she still carries damage from both of her eating disorders. She also expresses that she is grateful to now be able to eat the foods she loves. “I love to eat! I love food, but I was lucky not to be fatally affected,” Chung said.

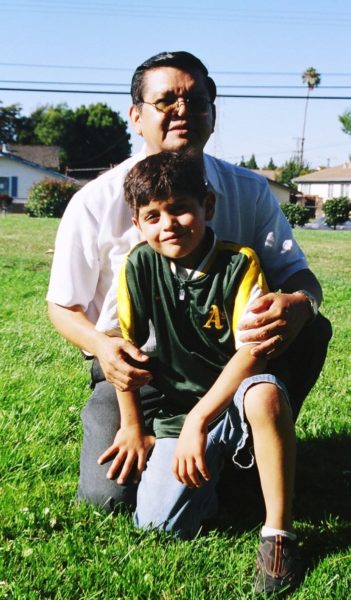

Chung has sometimes expressed concerns for students whom she fears may be going down the same path she had. Though she was worried about the outcome, Chung has stepped in and aided a few of her students whom she knew to be struggling with their eating habits. “I was afraid to say something wrong. I was mortified to see one of my students in front of me going through what I went through,” Chung said.

Chung recognizes the sensitivity and trouble surrounding eating disorders at Menlo. Because of Menlo’s competitive nature, she expressed her concerns that stress and anxiety fuel eating disorders. “Some [Menlo students] are anxious about everything. When a teacher criticizes them, or they feel stressed, [some students] can use food to cope,” Chung said. She mentions that Menlo’s competitive environment can cause a need for “balancing out the stress.”

Moreover, Chung explains that being a perfectionist can only increase the sense of competition between students to be the best looking. “Menlo is so competitive. When people are perfectionists it adds to the problem,” Chung said.

Chung is grateful that there are many more resources for teenagers struggling with eating disorders today. “I am so happy to see now that there is a lot of progress made in this domain in treatment,” Chung said. She explained that because doctors can now point out signs and symptoms, she feels recovery can be more widely spread to eating disorder survivors. Chung also stresses that through treatment, it has become much easier to speak on this issue. With recovery comes acceptance.