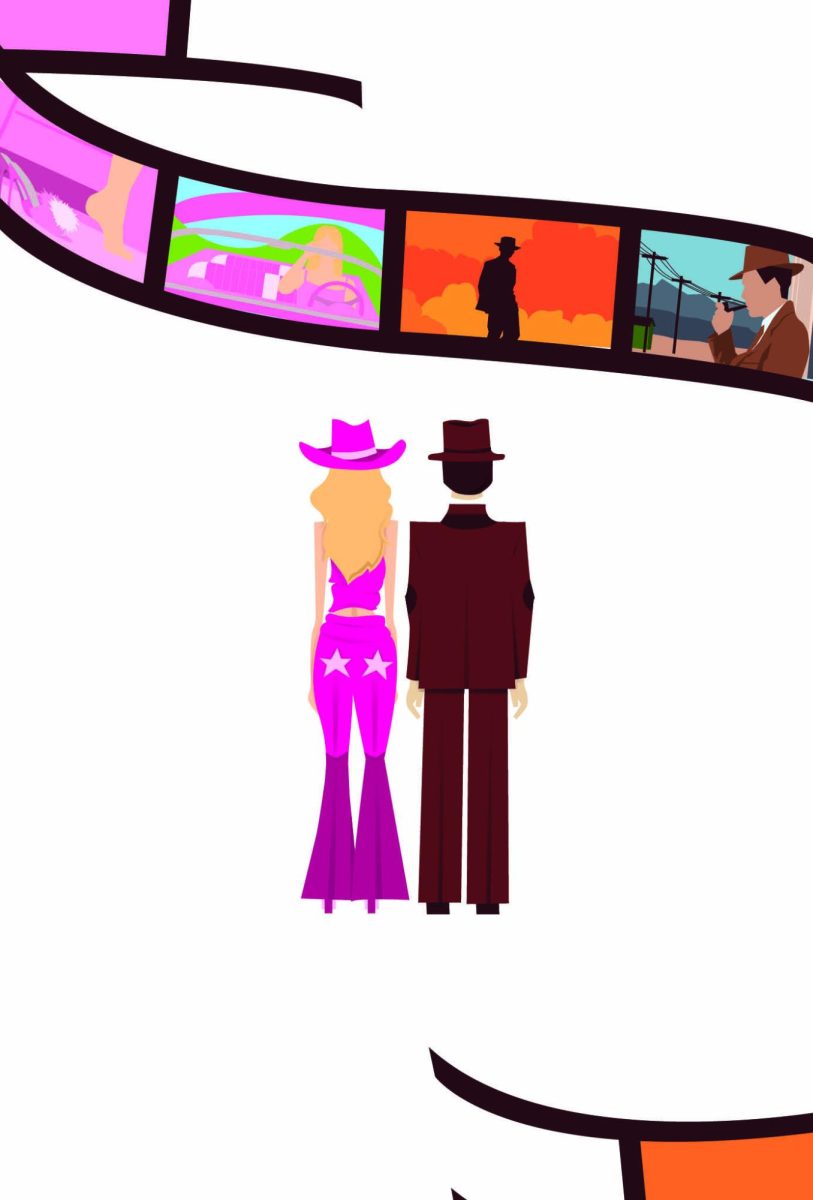

Barbie – reviewed by Caroline Clack, Video Editor

Barbie was inescapable throughout the summer. Mattel’s pink Barbie logo was around every corner –– appearing on billboards, in advertisements, and in commercials. Due to promotional partnerships, the Barbie franchise painted the world pink. Since the doll carries complicated emotional baggage, it’s fitting that the Barbie Movie is also complicated. But the way the movie addresses the doll’s complex past made it a fun summer blockbuster with an inspiring message that all ages and genders should watch.

Originally, Barbie and what she stood for was complicated. On the one hand, Barbie and her various accomplishments presented an aspirational image of a fashionable, young woman. On the other hand, Barbie’s unrealistic and sexualized appearance –– a high-heeled, swimsuit-wearing, blond woman with big breasts and a tiny waist –– led critics to question the doll’s impact on a girl’s self-esteem.

Over the course of the doll’s existence, Mattel has failed to separate Barbie from the stigmas surrounding the doll. As the company continued to face scrutiny over Barbie dolls, CEO Ynon Kreiz proposed a plan to pull the company out of its dire financial situation. This solution? The Barbie movie.

Because of the controversy surrounding the doll, producers of the movie needed to approach the film carefully. The movie couldn’t be a satire, as Mattel needed Barbie dolls to sell, but it also couldn’t be a shameless advertisement either.

To increase the film’s credibility, Mattel selected director and award-winning actress and director Greta Gerwig, who formulated multiple goals after signing onto the project –– she wanted viewers to experience laughter and joy while also feeling challenged emotionally. She also wanted viewers of all gender identities to feel partially relieved of the pressure that comes with walking on an impossible tightrope of perfection.

Gerwig accomplished her vision for the film in two ways: by exploring the damaging effects of patriarchy and perfectionism while also encouraging women to embrace the struggles and joys of being a woman.

The Barbie movie’s exploration of the social construct of patriarchy sheds light on the societal issues that viewers should focus on. When Barbie first steps into the real world, she is instantly dismissed, a scene female viewers connect with and one that allows male viewers to see what it’s like to be overlooked because of gender. Despite progress, patriarchy’s presence still affects today’s culture. By recognizing the harmful effects of patriarchy in a way that makes viewers empathize with its victims, Barbie encourages viewers to reject the social system and construct a new, inclusive ‘normal’ for men and women to thrive.

Barbie also addresses the concept of perfection. At the beginning of the film, Stereotypical Barbie (played by Australian actress Margot Robbie), is as inauthentic as her plastic surroundings. Her perfection limits the audience’s ability to connect with her. Viewers find Barbie relatable when she embraces her imperfections, because being messy is a fundamental part of being human. Gerwig reminds audiences that imperfections don’t negate our value as people, but amplify it.

The final important detail of the movie is the way it embraces the difficulties of being a woman. In the movie, Gloria (America Ferrera) is a Mattel employee struggling to connect with her daughter, Sasha. The movie uses her character’s perspective on womanhood to recognize the fact that, as a woman, it’s unrealistic to make everyone happy. Instead, women should embrace the unfair, understand they are not alone and live happily while rejecting the expectations of a complicated system.

Despite all of the valuable lessons Barbie teaches its viewers, the movie initially faced significant backlash. The Barbie movie playfully explores modern social issues, including the problematic aspects of the doll’s history. Many critics took the acknowledgement of the persistence of certain social problems as the movie’s tacit perpetuation of these structures. These perspectives miss the point of the film, which was not to present a perfect world so much as it was to explore a complicated one.

Barbie encourages viewers to celebrate successes achieved in a complex society. Though Gerwig emptied the paint company Rosco’s worldwide stock of pink paint, she did not attempt to simply paint over Barbie’s past faults. Instead, the movie succeeds in making women feel empowered by their female identity in the moment and going forward.

Oppenheimer – reviewed by Jake Abrams, Guest Writer

Christopher Nolan, the director of “Oppenheimer,” began writing the movie immediately after reading the Pulitzer Prize-winning biography “American Prometheus” in early 2021 (yes, a movie of this magnitude took only two years to make). His status in Hollywood is unparalleled: any movie he wants to make, of any length and budget, will be produced. So why did a British filmmaker choose to make a movie about an American hero who died over half a century ago?

Sure, “Oppenheimer”’s subject matter offers an opportunity to capture gorgeous visuals and, thanks to Nolan’s technical meticulousness, the three-hour biopic’s photography delivers. Most of the movie was filmed on IMAX cameras and effects were done with in-camera editing. That means there’s no CGI, so the film stock doesn’t lose quality when converted to digital, thus creating stunning images. Because of the absence of CGI, there’s also a wow-factor to the beauty of each frame –– how did they produce this shot? How did they set it up?

Cillian Murphy’s performance as the titular character has rightfully been receiving praise long before the film hit theaters. Given just around half a year to prepare for the role, Murphy’s commitment is impressive. It’s the little things: the way his voice ages along with his character, his body language and posture –– even his hands-on-hip slouch is telling –– and his frozen blue eyes conveying the troubled psychology of Oppenheimer.

A small detail that elevated the film was how Nolan’s direction and Murphy’s performance consistently portrayed Oppenheimer as a thoughtful, troubled man. The film didn’t change after the atomic bombings; the eerie tone never shifted. You got the sense Oppenheimer was always careful of his genius –– even in his college days –– and the bombings merely revealed his true self. For Oppenheimer, and all tragic heroes in stories, fate is omnipotent, creating a chilling inevitability to their demise. But he does change in certain ways. He transitions from a shy student to a confident Los Alamos lab director to a scarred political figure, but the similarity between the opening and closing shots (both of Oppenheimer staring into raindrops hitting water, the ripples resembling atomic explosions) convey that the fear of his genius was always within.

The supporting characters are intriguing as well: Benny Safdie as Edward Teller, Jason Clarke as an Atomic Energy hearing judge, Robert Downey Jr. as Lewis Strauss, and even Garry Oldman as Harry Truman for 90 seconds were captivating. Are you noticing a theme? Where are the women?

Emily Blunt, who played Kitty, Oppenheimer’s wife, and Florence Pugh, who played Tatlock, his mistress, turn in fantastic performances, but are ultimately stunted by poor writing. Nolan’s a talented artist, but if he has a glaring weakness in his films, it’s writing female characters.

In one scene, Kitty, though she is married, drunkenly flirts with Oppenheimer; in the next, they’ve a child, and the next, Oppenheimer comes home to find her drunkenly screaming over their baby. The movie spends little time exploring her side of the relationship with Oppenheimer or her motives, leaving us with a singular impression: she’s unhelpful, a drunk, and her character only exists to progress Oppenheimer’s character.

In the final act, during the climax of the court scene, Kitty delivers a powerful monologue satisfying enough to garner applause as it’s spoken, but it feels out of place. Nolan didn’t care to explore Kitty earlier, the audience doesn’t care to connect with her. When she has her powerful scene –– which I won’t spoil –– we’re only satisfied because it directly benefits Oppenheimer; we’re cheering for him, not her. Ideally, you’d want the audience to care about both. It is Kitty’s scene, after all.

Unfortunately, Kitty’s character isn’t even the shallowest of the female characters. When reading up about the film after watching it, I discovered Jean Tatlock, a prominent supporting character, is a physician and psychoanalyst. The only way I would have been able to describe her was Oppenheimer’s side piece. Who hates flowers. It is true that supporting characters are there to, yes, support the main character, but without thorough exploration, they come off as flat. It’s even more concerning that this issue is mainly with the women. Pugh does a nice job, similar to Blunt, trying to add depth to their poorly-written characters, but it isn’t enough to save them.

Yes, the film has its few troubles, but ultimately, Nolan’s precision and talent creates a classic. What truly elevates any work of fiction is its awareness. Why does this story need to be told? Why now? Why to this audience?

Nolan, a Brit, is interested in a blatantly American (hell yeah!) subject. So…why? He began his screenplay during the pandemic, a time where interaction was limited and technology was everyone’s way of living. If the Wi-Fi was out, your day was probably ruined. AI was on the rise, with popular programs such as ChatGPT emerging at the pandemic’s end.

Technology is the atomic bomb of our times: while universally accepted as dangerous, it’s unregulated. Silicon Valley geniuses create new, scary, brilliant programs weekly. Sure, technology is done under the impression it’ll make the world a better place (and also give a few people a lot of money), but those in charge must also be aware of the power they hold and the devastation they can cause.

Oppenheimer is a cautionary tale, one warning us of the power of extreme intelligence and drive, one warning us to honestly explore intention versus output. It’s not just a wildly-entertaining, visually-stunning theater experience, but also a story of a hero relevant today.

But, seriously, go see this while it’s still in theaters.